May 21, 2021

Suzanne Mallare Acton, a genre-defying conductor whose exacting musical standards and

knack for experimentation transformed Rackham Choir, is stepping down as the choir’s artistic

director after 25 years.

Acton will continue to be music director/conductor for future performances of Too Hot To Handel

and will remain as a mentor to promising young singers in Rackham’s high school vocal

internship program. Joe Jackson, Rackham’s long-time accompanist, is also leaving the choir,

and will also continue to work with Rackham interns.

Rackham is among the oldest vocal music groups in metro Detroit. Founded in 1949 with high

musical ambitions, the choir for a time performed regularly with the Detroit Symphony

Orchestra. But by the time Acton took over, the group was turning over musical directors and

had lost much of its musical firepower.

In 1996 when Rackham lost its director a couple months before a scheduled performance of

Handel’s Messiah, one of Rackham’s board members approached Acton to help them out by

conducting the concert. After the performance, the entire board overwhelmingly encouraged her

to stay on.

Acton agreed, jumping at the opportunity to experiment with choral music outside of her work as

Michigan Opera Theatre’s Assistant Music Director/Chorus Master. She quickly began pushing

the choir’s musical standard upward, reducing the number of annual concerts, imposing stricter

auditions for singers, and attracting new members to the ensemble.

“I want singers to communicate text, to really reach out to their audience, to do more than just

stand there and sing,” Acton said. “Just standing and singing is a little boring. I looked for

repertoire that would bring choral music to life.”

With Acton at the reins, Rackham stepped out of its comfort zone with performances such as

African Sanctus, a multi-media performance including composer David Fanshawe’s

photographs of Africa; a staged version of The Reluctant Dragon, a 1941 Disney film, with fullsize

puppets; and “Let My People Go! A Spiritual Journey Along the Underground Railroad,”

which was staged with actors, dancers, soloists and drummers.

through a jazz-gospel lens.

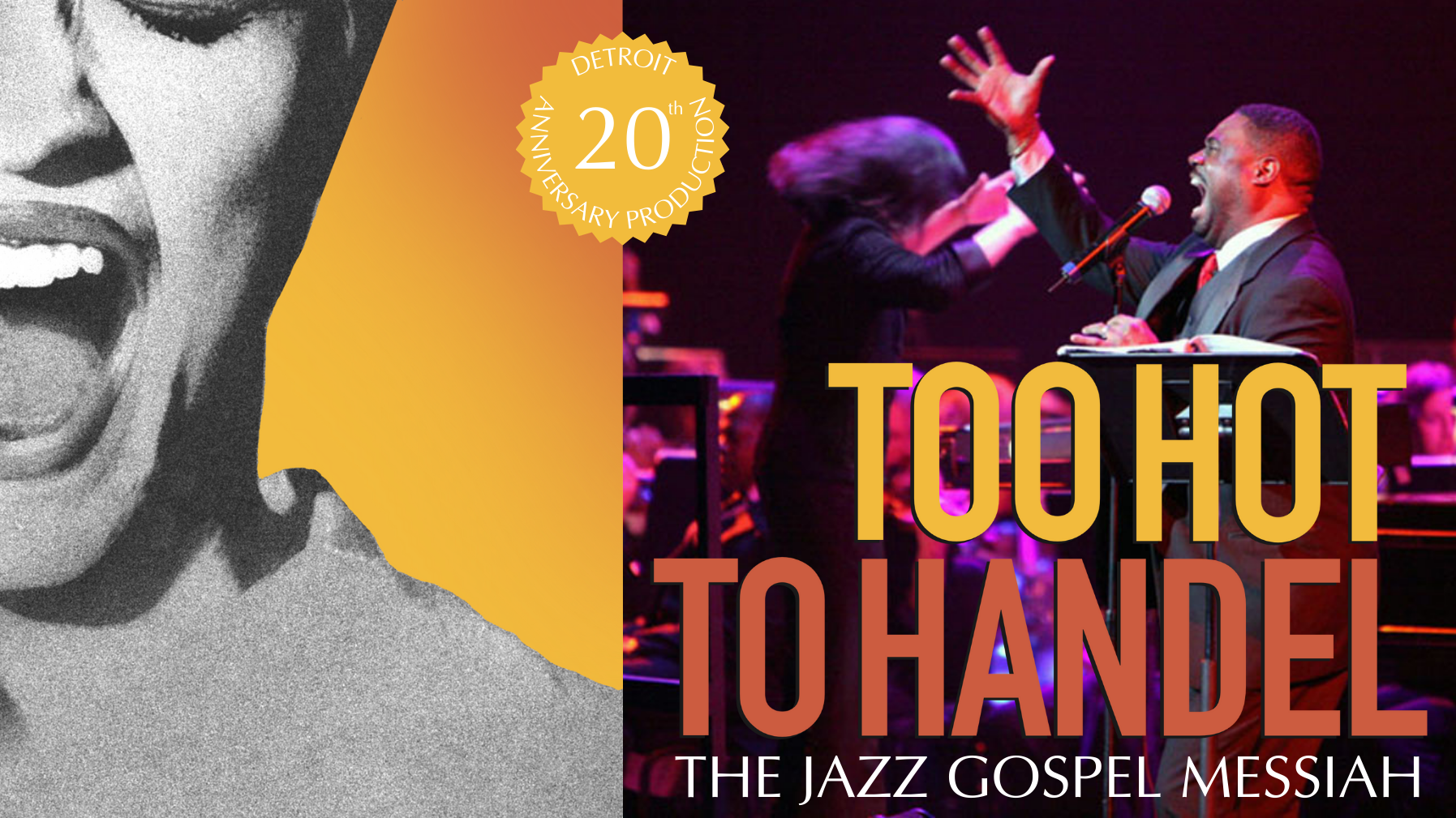

Acton’s most durable and popular innovation was Too Hot To Handel, a gospel-infused remix of

the Messiah that debuted in New York City in 1993. The Messiah is one of the most commonly

performed pieces of choral repertoire in the world, and it was a staple on Rackham’s annual

calendar. After conducting the classic in 2001, Acton went out to dinner with one of the soloists,

tenor Rod Dixon, and mentioned in passing that she’d been hearing rumblings about a new jazz

and gospel remix of the Messiah.

Dixon reached under the table, where he had the score in his bag. “I said, I just finished singing

it a couple of weeks ago!” he recalled.

Acton began planning to bring the show to Detroit, and Rackham performed it for the first time in

March, 2002 at the Little Rock Baptist Church. Acton invited David DiChiera, Founder of

Michigan Opera Theatre, to attend one of the performances, and he was so impressed by the

experience that he agreed to present it at the opera house in December, 2002.

Too Hot was received exuberantly at the Detroit Opera House, especially when people in the

crowd realized they could holler and clap along with the music. Over the next 20 years of

performances, Too Hot has regularly sold out, expanding Rackham’s profile and attracting new

members. In 2008, the choir received the Governor’s Award for Arts and Culture under her

leadership.

Dixon, who has soloed in dozens of performances of Too Hot, said Acton’s broad musical

sensibilities are a cornerstone of the show, calling her the “quintessential American conductor

who has a universal sense of high standards in music from all corners of the world.”

By bringing jazz and gospel sounds to the opera house, Dixon said, the show honored Black

musical forms that form the bedrock of American music but have been long excluded by

American cultural institutions.

“Suzanne could have very easily stayed behind the doors of the Michigan Opera Theatre and

stayed on the European side of music,” Dixon said. “She could have done that and been just

fine. But as a human being, she included us. As we evolved, she evolved.”

Acton was raised in a household of musicians, and her two older brothers introduced her to

jazz. (Both brothers have played saxophone in Too Hot.)

Acton excelled at the piano, which led her to accompany choral music since her youth. One of

her early mentors, John Wustman, accompanied opera stars including Luciano Pavarotti and

Elisabeth Schwarzkopf.

Though not a singer herself, Acton emerged from her training an expert in the workings of the

voice. Rackham members often remark that rehearsals feel like a top-notch voice lesson.

“If I’m struggling with a piece, she can fix what’s wrong in five minutes,” said Victoria Bigelow, a

soprano who has been with the choir for more than two decades. “Her ability to do that in real

time with a group of 80 people is incredible. I just think she makes us better at what we do.”

Dozens of promising young singers have benefited from Acton’s teaching through the Rackham

intern program, which gives high-schoolers a spot in the choir and one-on-one instruction on

solo repertoire.

Dominik Belavy, a baritone, interned with the choir in 2011 and 2012 before studying at the

Juilliard School.

“It was the most in-depth work I’d done on language and on musicality and on style,” Belavy

recalled. “I found out when I went to conservatory that my work with Suzanne mirrored

professional-level coaching.”

Acton’s mentorship didn’t end when he left for college, he said. A decade later, as he enters the

early stages of his professional singing career, she still passes along job opportunities.

“Suzanne has left a lasting legacy with the choir that we’ll continue to build on for a long time,”

said Emily Eichenhorn, president and managing board member for the choir. “We wish her well.”